Pappachan B, Alexander M (2006) Correlating facial fractures and cranial injuries. Haug RH, Prather J, Indresano AT (1990) An epidemiologic survey of facial fractures and concomitant injuries. King RE, Scianna JM, Petruzzelli GJ (2004) Mandible fracture patterns: a suburban trauma center experience. Hwang K, You SH (2010) Analysis of facial bone fractures: an 11-year study of 2,094 patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 17(2): 109–117 Liu-Shindo M, Hawkins DB (1989) Basilar skull fractures in children. A prospective study of 100 consecutive admissions.

Acad Emerg Med 7(2): 134–140Ĭhee CP, Ali A (1991) Basal skull fractures. Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, Pepe PE (2000) Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in U.S. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

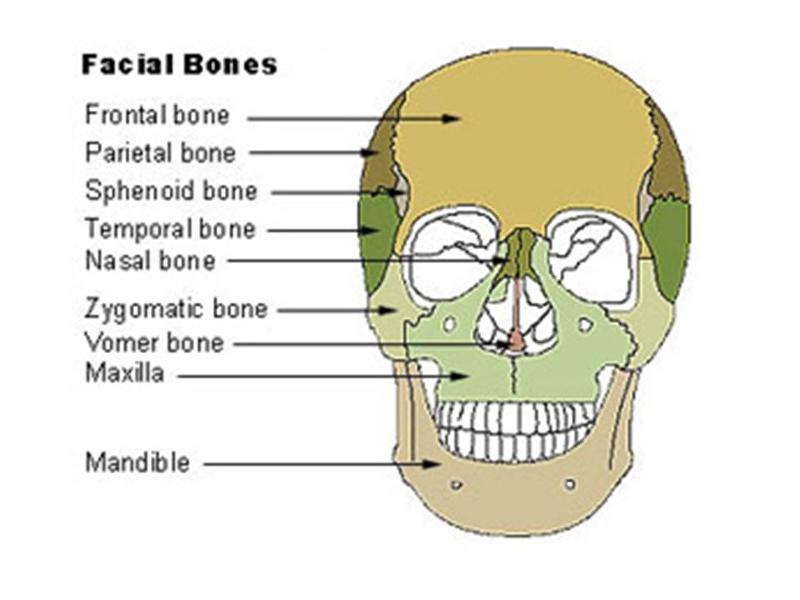

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. These risk functions are restricted to skull fracture and maxilla/zygoma injury assessments. The chapter concludes with an outline of the available, but limited, information on injury risk functions for skull and facial bones. These studies show that impact and fracture response is strongly dependent on location, bony impact geometry, and contact area. Discussion includes a detailed description of the available research on impact tolerance of skull and facial bones. The chapter begins with a discussion of biomechanically relevant anatomy and a discussion of injury severity scales for skull and facial fracture. This chapter outlines existing research on the impact and fracture response of the skull and facial bones including the calvarium, maxilla, zygomatic bone, nasal bone, orbit, and mandible. The skull and facial bones are biomechanically complex.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)